Project #6: Scheme Lab

Due date and time: Friday June 3, 6:59pm

This project is to be done in pairs using the "pair programming" technique

Introduction

For this project, you're being asked to write six Scheme functions according to the given specifications. This will give you the opportunity to practice functional programming and, in addition, learn more about how to approach and solve problems using recursion, a skill that will continue to benefit you in ICS 23 / CSE 23 and beyond, even if you don't ever write another line of Scheme code again. Functional programming is something you're likely to see again in your coursework if you take a course in programming languages (e.g., CompSci 141 / CSE 141), and functional programming features are gradually beginning to work their way into more mainstream programming languages, for a variety of reasons, so knowing something about it will make you more prepared to keep up with the inevitable changes in programming languages over time.

Choosing a partner

Before going any further with the assignment, choose a partner from among the people in lab with you. (It's fine, even preferable, to read this project write-up on your own ahead of time, though, so you and your partner can hit the ground running in lab.)

If you're having trouble finding a partner, notify your TA, so that you can be assisted in finding one. If you have not found a partner and notified your TA of the pairing by the end of Friday May 27, you will be assigned a partner and notified via email; once your TA has selected a partner for you, we will not allow you to switch to another one.

You will not receive credit on this assignment if you work on it alone, without the prior consent of the instructor. (Please note that "prior consent" does not include approaching us the day the project is due, having completed it on your own, and telling us that you haven't been able to find a partner.)

Using Racket

While there are many Scheme environments available (some free, others not), they tend to differ, often in subtle ways. So, as a standard for this course, we will use an environment called Racket, which the TAs will use for grading your project. Racket is notable for its support of several different graduated subsets of Scheme targeted at students, each one more complete than the previous one; we will be using one of these for our work here. If you use another Scheme environment, or if you have prior experience with standard Scheme, you will discover some differences between full, standard Scheme and our chosen subset. The best advice is to stick with Racket for this project.

Racket is a Scheme environment built primarily for use in teaching programming. It runs on all versions of Windows, Mac OS X, and various flavors of Unix and Linux. Racket is already installed on the machines in the lab, and it can be downloaded free for your use at racket-lang.org. The latest version, as of this writing, is 5.1.1, though new versions come out somewhat regularly; the explanation below assumes that you're using that version. (Previous versions are essentially the same.)

Installation of Racket on Windows is a snap. (I haven't installed it on other operating systems, but I presume it's just as simple on the others.) Just execute the setup program and it will take care of everything. Once the installer is finished, you'll find a folder called Racket in the Programs folder on your Start menu. Select Racket from that menu, and off you go.

When you first execute Racket, you'll be prompted to choose a language from a list. Remember that Racket supports several different "strengths" of Scheme, each allowing some features and disallowing others, and each including a different combination of libraries and features. (If you're not prompted to select a language, you can also select one at any time by going to the Language menu and selecting Choose Language....) On the list of languages, under Teaching Languages, click How to Design Programs and then Advanced Student, then click OK. Finally, click the Run button near the top-right corner of the main Racket window. Now you should be ready to roll!

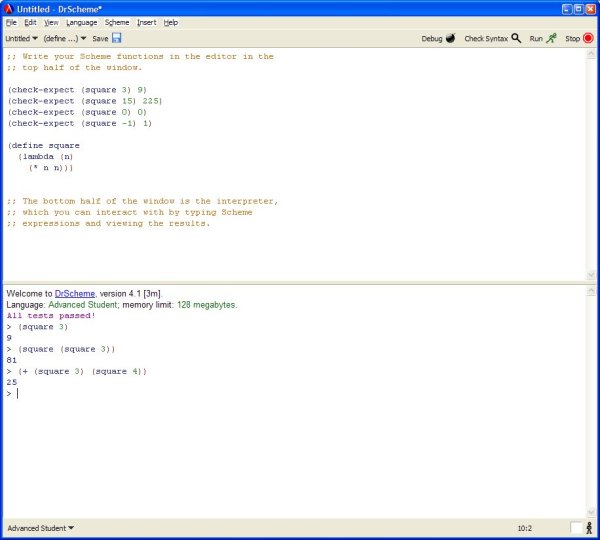

Below is a screenshot of Racket in action. (The version of Racket in the screenshot is a previous version, called DrScheme, but one that is more or less the same as the current one.)

The bottom half of the Racket window is the interpreter. Simply type an expression into the interpreter and you'll get back an answer, just like we talked about in lecture.

In the top half of the window, you can write Scheme source code and save it into a file. This is where you'll write the functions that you need to write for this project (and tests, too, if you're so inclined). When you make a change to your code and then wish to test it in the interpreter, click the Run button on the toolbar. This causes the interpreter to be restarted and all of the code in the top half of the window to be loaded (as though you had typed it all into the interpreter). So, in the example above, after writing the square function in the top half of the window, along with tests that verify its correctness, I clicked the Run button, and was told that all tests had passed, and was subsequently able to call the square function in the interpreter. Any output that's generated by any expressions — such as any tests you include — will be printed each time you say Run. (Don't forget to save your file periodically, so that you don't accidentally lose your work.)

The project

Below are a set of Scheme functions that you are required to write for this project.

In general, you are not permitted to make assumptions about the arguments to each function other than the assumptions listed in the description of each function. For example, unless explicitly stated, you may not assume that all lists will be simple — a simple list is one with no sublists.

Along with each function, you are required to write unit tests as we described in lecture, using Racket's built-in testing functions.

The tools at your disposal

Be sure that your code works in Racket with the Advanced Student language level selected; that's how we'll be grading your work. Beyond that, we're also staying within an even more restricted subset of Scheme. You may only use the following predefined Scheme functions or constructs in your solution:

define lambda cond else empty empty? first rest cons list list? = equal? and or not + - * / < <= > >=

You may also use these predefined test functions when unit testing your solutions:

check-expect check-within check-error

(You may not need everything listed above, but those are the only ones that you're eligible to use.) If you'd like to use any other predefined functions, you'll need to write them yourself, in terms of what's listed above.

Decomposing problems into smaller ones

Some of the functions below cannot be written easily without other "helper" functions. Turn in all of your helper functions along with the ones you are to write. You may reuse helper functions in more than one of your solutions if you'd like, though it isn't required. Similarly, you may call your solution to one of your functions in your solution to another.

A word about notation

The Advanced Student language level in DrScheme provides two equivalent ways of describing a list: using the list construct or a short-hand version consisting only of the lists elements surrounded by parentheses. For example, a list containing the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 can be written in one of two ways:

(list 1 2 3 4 5)

'(1 2 3 4 5)

These two notations can be a little confusing, because they sometimes require quoting in different places. For example, a list of symbols x, y, and z would look like this in each of the supported styles:

(list 'x 'y 'z)

'(x y z)

For your work, either of these styles is fine when writing your functions. When using the Advanced Student language level, as we will be in this project, the list construct is used to describe lists returned as output.

The functions

Here are the six functions you're being asked to write. Each includes a brief set of examples that shows what its output should be in a few cases; note that these examples are not intended to be a complete set of tests for each function, so you may want to develop a few extra examples. (Remember to pay special attention to the base case for each function, which is not always listed in the examples, but whose answer you should be able to deduce from the description of the problem.)

(fourth-element L)

The fourth-element function takes a list L and returns its fourth element. Of course, not all lists have four or more elements; if L is a list that doesn't, the empty list should be returned. L is not necessarily simple, but you shouldn't handle sublists differently from other elements (i.e., if the fourth element is a sublist, return the whole sublist).

Examples:

(fourth-element '(a b c d e)) => d

(fourth-element '(x (y z) w h j)) => h

(fourth-element '((a b) (c d) (e f) (g h) (i j))) => (list 'g 'h)

(fourth-element '(a b c)) => empty

(list-length L)

The list-length function takes a list L and returns the number of elements in the list.

Examples:

(list-length '(a b c)) => 3

(list-length '(a (b c) d e f)) => 5

(count-matches S L)

The count-matches function takes a symbol S and a simple list L of symbols and returns the number of times that S occurs in L.

Examples:

(count-matches 'f '(a b c d e f g)) => 1

(count-matches 'b '(a b a b a b a)) => 3

(count-matches 'x '(a b c)) => 0

(my-append L1 L2)

The my-append function takes two lists, L1 and L2, and returns the concatenation of L1 and L2. ("Concatenation" means to stick one on the end of the other.) Note that concatenation is not the same thing as what "cons" does to two lists.

Examples:

(my-append '(a b) '(c d)) => (list 'a 'b 'c 'd)

(my-append '() '(a b)) => (list 'a 'b)

(my-append '(a b) '()) => (list 'a 'b)

(is-increasing? L)

The is-increasing? function takes a simple list L of numbers and returns true if the numbers in the list are increasing as you read them from beginning to end, and false if they aren't. We'll define "increasing" according to the mathemtical definition of the word, where the numbers are increasing so long as they never decrease. (This is as opposed to what you might call "strictly increasing," where every number has to be bigger than the previous one.) As special cases, we'll consider one-element and empty lists to be increasing.

Examples:

(is-increasing? '(1 2 3)) => true

(is-increasing? '(3 2 1)) => false

(is-increasing? '(1 2 2 3 4 4 5)) => true

(is-increasing? '(1)) => true

(is-increasing? '()) => true

(remove-duplicates L)

The remove-duplicates function takes a simple list L and returns a new list with all of the duplicate objects in L removed.

Examples:

(remove-duplicates '(1 2 3)) => (list 1 2 3)

(remove-duplicates '(1 2 1 4)) => (list 2 1 4) -or- (list 1 2 4)

(remove-duplicates '(3 3 3 3 3)) => (list 3)

The last example is interesting, too. A lambda expression builds and returns a function. You don't have to give that function a name in order to use it, though we often do. In this case, we're saying "Call filter-items, passing it a newly-built function that takes a string and returns true if its length is no more than 4, along with a list of some strings." We expect to get back a list of all the strings in the original list whose lengths are no more than 4.

Grading

This project will be graded on a 18-point scale, unlike the previous projects have been. (Please note, though, that this project will not weigh differently on your final grade than the others; your score on this project will be scaled proportionally to match the others.) The 18 points will be broken down differently than the points available in the other projects. Each of the six Scheme functions will be worth three points and will be scored according to the following rubric:

- 2 points for Correctness and quality of solution:

- To earn a 2, the function must return the correct value (as specified) in all cases. We may test your functions on cases other than the examples listed, so make sure that you test your functions thoroughly.

- To earn a 1, the function must be correct in some but not all cases. The function's code must also constitute an attempt to actually solve the problem given. To be clearer about this, the following two situations will yield a score of 0:

- Your function works only on the base case (e.g., the empty list).

- Your function "accidentally" works on one of the cases, but doesn't constitute an attempted solution to the problem given (e.g., if your recursive-sum function always returns 3, and that happens to be the answer for one of our test cases).

- 1 point for Testing, which means that you used DrScheme's built-in test functions like check-expect to demonstrate that your function works in a variety of cases. To get 1 point, you must include interesting cases other than the ones listed in the project write-up.

- Note that Scheme is a much deeper, much more full-featured programming language than we've considered in class. (For example, there are predefined functions in Scheme that solve some of the problems that I've assigned you.) Still, because we're interested in learning how to solve problems in a particular way, we're sticking with only a small subset of Scheme. You are forbidden from using predefined Scheme functions or constructs that are not on the list of accepted functions and constructs listed at the top of this project write-up. Any of your functions that uses anything forbidden will receive 0 points. (If you're not sure if one of your solutions breaks this rule, please ask us ahead of time; this is not intended to be a "gotcha," but it is intended to force you to attack your problems in a certain way.)

Style and other issues will be de-emphasized, since we have not spent time discussing these issues with respect to Scheme.

Deliverables

Put all of your solutions into a single file called project6.scm. Submit this file and no others. We must be able to read this file directly into the Racket environment to test it, so don't write the procedures in Microsoft Word or another format.

Please include a comment at the top of the file that lists the names and student IDs of both you and your partner. Comments in Scheme begin with a semicolon character — though, by convention, we often use two of them in a row, so they're easier to see. Everything that follows a semicolon on any line is ignored by the Scheme interpreter.

Follow this link for a discussion of how to submit your project.

Additional challenge

For those of you who are interested in further understanding how functional programming is different from the object-oriented programming you're accustomed to — particularly, how giving up variables changes how we approach problems, but doesn't make them impossible to approach — consider the problem of implementing a queue in Scheme, using the tools we know about thus far.

A first attempt: queue as list

One approach would be to implement a queue as a list, with the following functions:

- make-queue, which takes no parameters and returns an empty queue (in this case, an empty list).

- queue-enqueue, which takes a queue and a new element and returns a queue with the new element added to the back (in this case, added to the end of the list).

- queue-dequeue, which takes a queue and returns a queue with the front element removed (in this case, the first list element is removed).

- queue-front, which takes a queue and returns the element at the front (in this case, the first list element).

- queue-empty?, which takes a queue and returns true if it's empty and false if not (in this case, we can check if the list is empty).

Once you had these functions, you'd no longer need to know how you implemented the queue; they collectively play the same role as an interface in Java, hiding the details of the queue's implementation. (Implemted this way in Scheme, the details aren't quite hidden, but you can safely ignore them, while using only these five functions to manipulate a queue.)

Try implementing these functions, then read on.

Analysis of our first attempt

Okay, now that you've implemented the functions, consider the O-notation for them, understanding that lists in Scheme behave essentially like singly-linked lists with head references.

- make-queue is O(1), because all it does is return an empty list

- queue-enqueue is O(n), because adding to the end of a list takes linear time

- queue-dequeue is O(1), because removing the first element of a list takes constant time

- queue-front is O(1), because accessing the first element of a list takes constant times

- queue-empty? is O(1), because checking if a list is empty only requires checking the head reference, which can be done in constant time

A better approach: using two lists instead

The issue that's keeping our first approach from being efficient enough for many purposes is that, in Scheme, lists are the equivalent of singly-linked lists with head references. Accessing the end of these lists — which we need to be able to do when we enqueue elements — is expensive. Unlike in Java, though, we can't just add a tail reference in functional Scheme. There is, however, a clever approach that is O(1) on the average (over the long haul). The analysis is a bit deep — it uses a technique called amortized analysis, which you'll learn more about in ICS 23 / CSE 23 — but I can give you the rough idea here.

Instead of using just one list, our queues will be made up of two lists:

- A list of the first i elements in the queue, beginning with the front element and continuing forward.

- A list of the last j elements in the queue, beginning with the last element and continuing backward.

We can implement a queue, then, as a list containing two lists. For example, the implementation-level view of a queue containing the elements a, b, c, d, e, f might be any of these (or one a few other possibilities):

'((a b c) (f e d))

'((a) (f e d b c))

'((a b c d e) (f))

Now, what's the point of splitting the queue into two lists like this? Think about how each function could be implemented now:

- make-queue returns a list of two empty lists.

- queue-enqueue takes a queue and a new element and returns a new queue with the following properties:

- The first list is unchanged

- The second list has the new element added to the front.

- queue-dequeue takes a queue and returns a new queue with the front element removed. There are two possibilities:

- If the first list has elements in it, the first element in the first list is removed and the second list is unchanged.

- If the first list is empty, make the first list be the reverse of the original second list (with the first element removed) and make the second list be empty.

- queue-front takes a queue and returns the front element. There are two possibilities:

- If the first list has elements in it, the first element of the first list is removed.

- If the first list is empty, return the last item from the second list.

- queue-empty? takes a queue and returns true if both of its lists are empty, false otherwise.

Try writing these functions, then read on.

A brief analysis of our second approach

Let's consider again the O-notation of each operation.

- make-queue is O(1), because two empty lists can be created in constant time.

- queue-enqueue is O(1), because we can add an element to the front of the second list in constant time.

- queue-dequeue is O(n) in the worst case, because it requires reversing the second list. The trick here, though, is that it won't happen very often. And the longer it takes to do — the longer the second list is — the longer it will be before we have to do it again, because we'll have a longer first list when we're done. On the average, over the long haul, the average time spent performing a dequeue will be a constant. (This analysis is similar to why the add( ) method that adds an element to the end of an ArrayList takes constant time on the average, even though it sometimes takes longer.)

- queue-front is O(n) in the worst case, but this only occurs when the first list is empty. Assuming that we don't ask for the front element any more often than we dequeue an element, the expensive calls to queue-front won't happen very often, and will happen decreasingly often the more expensive they are. (If you're going to need to call queue-front many times between queue-dequeues, there are ways to mitigate this problem.)

- queue-empty? is O(1), because it takes constant time to check if two lists are empty.

On the face of it, this analysis seems worse than what we started with — there are now two operations that can take linear time, while we had only one such operation before. The difference here is that, in our first attempt, every call to queue-enqueue takes linear time; in our second attempt, only occasional calls to queue-dequeue or queue-front are linear, and the rest are constant. So this really does turn out to be a truly better approach.

Acknowledgements

- Imported from Eric Hennigan's ICS 22 which was in turn adapted from Alex Thornton's version which he developed over many years.