Introduction

This study guide is a summary of the material covered in lecture since the Midterm. It should be noted that the Final Exam is cumulative. Though it will emphasize post-Midterm material somewhat over pre-Midterm material, all of the material covered in the course is fair game for the exam. Be sure to check out the Midterm Study Guide for a rundown of material covered before the Midterm.

The best advice for studying is to focus your attention as much on the "Why?" as the "What?" It's my goal to write an exam that does not depend solely on your ability to memorize terms, definitions, and facts; instead, I'm much more interested in whether you understand why things are the way they are, and in your ability to combine concepts we've learned about in novel ways that we've yet to consider in lecture.

I should point out that this study guide is not intended as a replacement for the lectures or your own notes. It's possible that something we discussed in class will have been left out of the study guide, but is still fair game for the exam. I'm not trying to cheat you on purpose, but the study guide is what it is: it's a guide.

Enjoy.

Assessing design quality

(This is a topic that we covered just before the Midterm, but that I inadvertently left out of the Midterm Study Guide. I've added it here, since it remains fair game for the Final Exam.)

One of the things that can be frustrating about software design is that it's difficult to assess whether your design is a good one. How much coupling is too much? How little cohesion is too little? How do I know whether concerns are being separated well enough?

Unfortunately, there is no one metric or set of metrics that we can use to determine, in black and white, whether our design is "good enough." But there are some well-known techniques that allow us to quantitatively assess certain aspects of our designs. Most notably, a fair amount of work has been put into assessing complexity. If we can measure the complexity of our design, we know something about its quality. (Notably, we don't know other things, like whether it meets its requirements; but we can test for those other things separately.)

Complexity measurements focus on choosing some attribute that contributes to the complexity of our design, then measuring something about that attribute. There are two kinds of attributes we can focus on:

- Intra-module attributes. Attributes of a single module.

- Inter-module attributes. Attributes of a collection of modules, taken together.

Intra-module attributes

There are at least two things we can measure about a module if we want to assess its complexity quantitatively:

- Size. Longer modules are harder to understand, harder to maintain, and likelier to have bugs. So measuring size tells us something about complexity.

- Structure. How we write something determines complexity, independent of its size. So we can measure aspects of a module's structure (e.g., loops, if statements, parameters, etc.).

Measuring size

The simplest way to measure size is to measure lines of code. Often, this is reported as thousands of lines of code (or KLOC, where K stands for "kilo-"), because a ballpark estimate to the nearest thousand, in a large project, is about as good as a perfect number. Lines of code is a simple enough metric, though it can be terribly misleading:

A more layout-neutral measurement of code size might be to count tokens instead of lines. Tokens are the individual words and symbols that have meaning in a programming language. For example, in this block of Java code:

public static void main(String[] args)

{

System.out.println("Hello world!");

}

there are a total of 21 tokens: public, static, void, main, (, String, [, ], args, ), {, System, ., out, ., println, (, "Hello world!", ), ;, and }. Notably absent from the list of tokens are whitespace (spaces, blank lines, tabs) and comments, making this a metric that has nothing to do with how the program is laid out. Unfortunately, despite its deficiencies, lines of code is a metric that seems to resonate better with programmers — we know what 100 lines of code "feels like," but have less of a sense of what 1,000 tokens feels like.

Measuring structure

Measuring the size of a module ignores the fact that the way we write our code is at least as important as how much code we write. Other complexity metrics focus on the structure of our code.

One such measurement is called cyclomatic complexity. The cyclomatic complexity measurement begins with the building a control flow graph, which depicts the possible flows of control from one line of code to another. For example, consider the following block of code.

public int nonsenseAlgorithm(int[] a)

{

1 for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++)

{

2 if (a[i] < 0)

{

3 a[i] = a[i] * -2;

}

4 else if (a[i] == 0)

{

5 a[i] = Integer.MIN_VALUE;

}

else

{

6 a[i] = a[i] * 2;

}

}

7 return -1;

}

Each line on which there is either a decision to be made or an action to be taken has been numbered, starting from 1. Note that the line containing the method's signature, the curly braces, and the line containing only an else are not numbered, since there is neither a decision to be made nor an action to be taken on any of these lines.

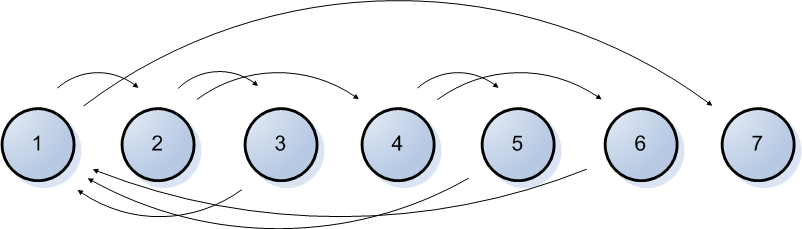

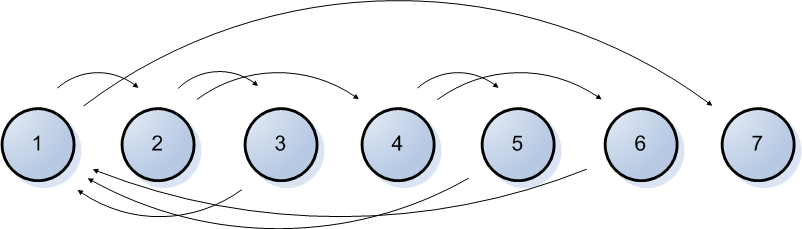

We can now draw our control flow graph by depicting each numbered line as a numbered circle called a node and each way we can get from one line to another as an arrow called an edge connecting two nodes. In the example above, our control flow graph would look like this:

The cyclomatic complexity measurement is calculated by counting nodes, edges, and connected subgraphs. Connected subgraphs are a subset of the nodes that are completely "connected" (i.e., if you look at it, there are no nodes that can't be reached when starting at line 1 and following edges). A single method will always be one single, connected subgraph; the control flow graph for an entire class with five methods would contain five, connected subgraphs, one for each method.

Given the number of nodes n, edges e, and connected subgraphs p, the cyclomatic complexity is:

- CyclomaticComplexity = e − n + p + 1

In the example above, we have seven nodes, nine edges, and one connected subgraph, so our cyclomatic complexity is:

- CyclomaticComplexity = 9 − 7 + 1 + 1

- CyclomaticComplexity = 4

Larger numbers indicate a higher complexity than smaller ones. For example, a larger number indicates that it will be more difficult to come up with a complete set of test cases to cover all possible paths through the control flow graph.

Inter-module attributes

We didn't spend time on this topic in lecture, though this topic is covered in some detail in your textbook.

Unit Testing and Test-Driven Development

What is unit testing?

In preparation for your implementation of the course project, we discussed unit testing. Unit testing is generally done performed by developers during the implementation of each module. The goal of unit testing is to focus a microscope of individual parts of the program (e.g., individual classes or even individual methods), evaluating how well they work outside of the context of the rest of the program.

No matter how much unit testing we perform, we can't be certain that our entire system is correct even if all of our unit tests pass, since unit testing ignores the issues that arise when different parts of the program are integrated together. But it does provide a way to verify that the individual parts themselves work — a condition without which the entire system certainly won't — in a context in which understanding the cause of a bug is much simpler than when testing the entire system.

Another benefit of unit testing is that it positively affects design quality. In order to ensure that a module can be tested in isolation, you will tend to have lower coupling, better separation of concerns, clearer naming, and so on. If unit tests are being written as the program is being developed, you will tend not to stray too far with a poor design, since writing unit tests will force you to clean it up sooner rather than later; the sooner you clean up the design of a module, the easier it is, since fewer other modules depend on it.

Unit testing is generally done in an automated fashion, with unit tests implemented as code. The major benefit here is repeatability; you can now run the tests as often as you'd like. By keeping the tests over the long run, we have a way to detect if the behavior of individual modules has changed in a way that causes these tests to fail later; if so, we can decide whether the change in behavior was expected (in which case the test is no longer valid) or not (in which case we've broken our code and should look into fixing it).

When we implemented unit tests in this course, we wrote them in Java using a tool called JUnit. I will not ask you to implement JUnit-based tests on the Final Exam, though I may ask you to read and understand them. See the code example from lecture for more details.

What is test-driven development?

We talked in lecture about test-driven development (TDD), a process for developing programs and their designs simultaneously. It centers on the following iterative process, which is focused on allowing you to take short steps from stable ground to stable ground, so that you have a working program (with tests to prove that it works) every few minutes.

- Choose a feature to work on, generally something so simple that you can accomplish it in no more than a few minutes.

- Write a test that verifies that the feature will work when you're done with it. In a sense, you're experimenting with your design before you write the code that depends on it; if you don't like the way your design works during this experiment, you can change it at no cost, since you don't have any code that implements it yet.

- Compile the test and watch it fail (or succeed, sometimes!).

- If the test didn't compile, write the minimum amount of code to make the test compile. Note that "minimum" means that we sometimes write things that we know will be wrong a little bit farther down the line.

- Run the test and watch it fail (or succeed, sometimes!).

- If the test failed, write the minimum amount of code to make the test pass; again, we're willing to write code that we know will be wrong later, since our goal in any iteration is to make only the current test pass (while keeping all old tests passing, as well).

- Run the test again and (hopefully) watch it succeed.

- If the test failed again, go back to step 6; if it succeeded, you're on stable ground again!

After each iteration, we also consider ways that we can improve our code by "refactoring" it. Refactoring improves the design of a program without changing what it does. When we see things that could be designed better (such as duplicated code that could be eliminated or names that could be improved), we attack the problem right away, knowing that our tests can be run any time we want to know whether our code is still working as it did. If we mess up while refactoring, our tests will tell us so.

Note that while unit tests are a central task in TDD, you don't have to use TDD to make good use of unit tests.

Serialization

One of the requirements that you faced in the implementation of the course project was saving the program's data into a file and then loading it back up again, the goal being that the program could be stopped and restarted without any data being lost. This is a fairly common problem, so there is well-known terminology that describes the solution to it.

We say that serialization is the process of taking a set of objects and turning them into a single sequence of bytes or text. Deserialization, then, is the process of taking that same sequence of bytes or text and turning it into a set of copies of the original objects you started with. At first, this technique sounds a little strange, but it's actually very useful. Note that a file consists of a sequence of bytes. When your program sends or receives data across a network, it's a sequence of bytes being sent or received. So serialization and deserialization can be used to save objects into a file and load them back up again; it can be used to send objects across a network and then reconstruct them on the other end; and so on.

The details of Java's built-in implementation of serialization are beyond the scope of the Final Exam, but I would like you to understand what serialization is and what problem it solves.

Test cases and test coverage metrics

In general, there is no way to completely test a chunk of code (i.e., call every method with every possible set of inputs and verify the correct ouptut), simply because the number of possibilities is vast, even for relatively simple methods. So, instead, we are forced to choose a representative set of test cases, with the goal that they cover everything that's "interesting" about the chunk of code being tested. A test case is at least three things: a set of inputs, an action to be taken, and the expected output.

We say that test coverage is an indication of how thoroughly a set of tests verify the correct behavior of our code. We talked in lecture about test coverage metrics, which are quantitative ways to assess whether your set of test cases is sufficient. In particular, we talked about ways that, given a control flow graph, we could determine whether we had sufficiently tested the code that it represented.

Since we can't achieve complete testing, we talked about three different goals one could try to attain — three different test coverage metrics — each requiring more thorough test coverage than the last.

- Node coverage. Every node in the control flow graph is reached during the execution of at least one of the tests.

- This means, essentially, that every statement in the program is reached at least once.

- Not achieving node coverage means that there are some parts of our program that we never tested at all.

- On the other hand, achieving node coverage is often not sufficient. In a method with multiple, separate if statements, node coverage might be achieved with only a couple of tests, but different combinations of these if statements haven't been tested.

- Edge coverage. Every edge in the control flow graph is followed during the execution of at least one of the tests.

- This means that every "branch" (i.e., every way to get from one line to another) in the program is followed at least once.

- This is more thorough than node coverage, since we're not only considering each line, but different ways of reaching each line.

- We're likelier to see problems with our logic this way, especially in the presence of many if statements and/or loops.

- Path coverage. Every path through the control flow graph is followed during the execution of at least one of the tests.

- This means we're considering every possible sequence of lines that we could follow from the beginning to the end of the method.

- This is more thorough than edge coverage, since it considers all possible ways to pass through each edge.

- The number of tests required to achieve path coverage explodes exponentially as the number of conditionals increases, since we have to consider every possible way of passing through the conditionals.

- One interesting question is how we should deal with loops, especially those that might potentially run many times (or even forever). A typical way to deal with this is to require a few different numbers of iterations (e.g., zero (if possible), one, an average number, and a maximum number).

Tools can automate these kinds of test coverage metrics. Java, for example, allows for "instrumentation" (i.e., code that is triggered by the inner workings of the Java Virtual Machine). We could write a tool that builds a control flow graph for each method, then run all of our unit tests while watching which nodes are edges are reached; from this, the tool could report node, edge, and/or path coverage to us, as both a percentage (e.g., "80% of the nodes were reached") and a detailed listing (especially of those nodes, edges, and paths that were missed).

Quality assurance and testing

In many organizations, there is a department or group called Quality Assurance (QA), which is tasked with, as the name states, assuring the quality of the system. As we've seen, "quality" is a broad term, encompassing not only things like correctness (i.e., the system meets the stated requirements), but also whether the requirements are the right ones in the first place. While it is safe to say that issues of quality often crosscut the entire organization, QA teams are the ones who spend the vast majority of their time focused on assessing it.

It's generally wise for the QA group to answer to different people in the organization than a software development group, since their goals often oppose one another and there should be a management-level champion of each set of goals. For example, hen asked "Should we ship the system as-is?," software development will often want to say "Yes" even when the answer should be "No," if there is pressure on them to deliver by a certain date. It's important for QA to be able to weigh in with a reasoned opinion about why the answer should be "No."

Testing

One of the primary roles of a QA group is to plan and perform testing. We spent a fair amount of time in lecture talking about testing from several different angles.

Testing is the process of determining whether software meets its specification. It is done by planning and executing a set of test cases. Our goals are simple:

- Detecting the presence of problems.

- Identifying the cause of those problems.

There is some standard terminology used to describe the problems found during testing:

- Error. A mistake made by a person when working on a software system

- Fault. A problem with the software that arises because of an error

- Failure. Behavior of the system that does not match specifications, due to a fault.

Note that not all errors lead to faults and that not all faults lead to failures. It's the failures we're most concerned about finding; when we find them, we also have to diagnose it, which means finding and correcting the fault and (ideally) deciding the cause of the error, so that we might be able to introduce measures to avoid it in the future.

Testing is best done throughout a project, with different kinds of testing (focused at different levels of depth) done at different times.

- Unit testing, which is commonly done by developers during implementation of individual modules

- Integration testing, which focuses on testing how modules interact with one another

- Acceptance testing or User acceptance testing, in which users determine whether the software meets their own needs

White box vs. black box testing

We can distinguish between two kinds of testing, each focused differently:

- White box testing, or structural testing, in which we choose test cases based on the structure of the code. Unit testing is a form of white box testing. We can also do white box testing by devising tests of our complete system, driven by code that we want to test.

- Black box testing, or specification-based testing, in which we test the system without regard for its source code, by experimenting with the behavior of the complete system. Test cases are generally selected based on the requirements specification.

The tradeoff here is between the difficulty of needing to understand the source code and the difficulty of systematically choosing and automating specification-based tests. Because of the need to understand the source code, white box testing is often best done by developers, while black box testing is often best done by others, so that ingrained bias of the developers can be overcome.

Equivalence partitioning and test matrices

Whether you're focused on white box or black box testing, there still remains the problem of deciding on a set of test cases. Rather than just choosing test cases somewhat randomly, as we think of them, one way to focus our minds and be sure we're covering a variety of interesting circumstances is to do equivalence partitioning, which proceeds according to the following steps:

- Identify a set of inputs (maybe all possible inputs, maybe just some)

- Identify a basis for subdividing the input

- Examples include the size of a collection, the order in which the collection's elements appear, conditions that may or may not be true (e.g., the user is already logged in)

- Divide the set of inputs into subdomains using this basis.

- Each of these subdomains forms an equivalence partition, meaning that each input in the subdomain is equivalent in some sense.

- Each possible input is a member of one or more of the subdomains; it's fine for them to overlap.

- Select representative test cases from each of the subdomains, along with test cases that belong to multiple subdomains whenever possible.

If we follow this procedure for many interesting bases, we tend to have a very good set of test cases.

Test oracles

A test oracle is a mechanism for deciding whether a test case has failed or succeeded. Oracles are critical to testing, since we can't have meaningful test cases without expected output.

How we create test oracles depends on the formality of our specifications. When our specifications are very formal (e.g., including, say, mathematical formulas), we can use these formulas to automatically generate our expected output; we say, then, that our test oracle is this set of formulas. For a variety of reasons, formal specifications are relatively rare — they're difficult to develop, harder to understand, expensive — so we're generally left to decide on our expected output manually. In such cases, the test oracle, ultimately, is us.

Staged releases and user testing

Despite a team's best efforts to test a product before delivering it to customers, it is generally not possible for the team to test every possible scenario that will arise once the customers begin using the system. Users may have needs that were never discovered during requirements elicitation, may respond to changing business requirements by trying to use the existing system differently, and are notorious for attempting things that no one ever imagined.

It's been increasingly common for systems to have staged releases, where a sequence of pre-releases are distributed to users, with the confidence level in each pre-release being higher than the previous one and the number of users accepting it generally rising from one to the next. While there is not one standard nomenclature, the following sequence of pre-releases has evolved into a fairly common one:

- Alpha (or alpha testing), where users accept a version that is either incomplete or not fully tested. Users get to experiment with new featurues while accepting the fact that the software will not always perform as well as advertised.

- Beta (or beta testing), which generally coincides with the software being "feature complete" and having gone through substantial testing. Users have a higher level of confidence than they would in the alpha release, though there are still issues that will be discovered.

- Release Candidate (RC), which is used to denote a version that could be the final one. It is distributed to as many users as possible, with the understanding that the final version will be exactly the same unless important problems are found. RC releases are quite often very stable and almost indistinguishable from the final product.

Version control systems

When multiple people work together on a project — sometimes all in the same physical location (e.g., the same building), sometimes geographically distributed — there are coordination issues to be dealt with. Each person might have a copy of the project on his or her own machine, yet changes need to be shared so that each person can see the results of the others' work (at least when it's important). The effort required to manually synchronize the effort of many people increases much more than linearly as the number of people increases; before long, you have an unmanageable mess, unless you employ tools that help.

Version control systems (sometimes called source control systems or source control management systems) are tools that help solve this kind of problem. There are many version control systems in popular use, but most share the same basic philosophy, even if they differ (sometimes substantially) in the details.

When using a VCS, there is generally a central repository (in the sense of the "repository" architectural style we saw earlier this quarter), in which a complete, up-to-date copy of the system is stored. Usually, along with the most up-to-date version, is stored a database tracking all of the changes that have been made to the system, so that it becomes possible not only to say "Give me a complete copy of the system's source code," but also to say "Give me a complete copy of the system's source code as of April 1."

The repository may be available on an intranet (i.e., within an organization) or the Internet, depending on the geographic reach of a project and whether the source code is proprietary. Users connect to the repository when they want to get the latest version of the code, or when they want to publish their changes. A few typical operations provided by a VCS are:

- Check out. This generally means that you are downloading a version of the system (or some part of the system) from the repository. On some systems, this also means that you're locking one or more files so that no one else can publish changes to them, though this is rare nowadays.

- Check in or Commit. This generally means that you are publishing changes into the repository so that others can see them. Changes are generally grouped, so that a set of related changes to different files become one changeset. Associated with each changeset is generally a comment (sometimes called a changelog) which explains what has changed and, more importantly, why.

- Compare. This allows you to see, often visually, how your version of some file differs from the version currently available in the repository, or to see how two different versions in the repository are different. This can be useful to help you to understand the history of changes that have been made to a particular file, or to understand the scope of the changes you're currently making.

When multiple people are working, there can still be issues, even when there is a VCS involved. For example, consider the following scenario:

- Developer A checks out version 10 of file X.java and begins making changes to it. (Assume that checking it out means that it is not locked; anyone can still modify it.)

- Developer B checks out version 10 of file X.java and also begins making changes to it.

- Developer B finishes her changes, so she commits them. X.java is now at version 11.

- Developer A finishes his changes, so he wants to commit them. But the VCS reports that the version of X.java now in the repository doesn't match the version he checked out.

At this point, Developer A will need to merge his changes with Developer B's. There are tools that help with this kind of task, but it can't be fully automated, since there exists the possibility that the two sets of changes are incompatible with each other; at this point, a conversation may need to take place before a decision can be made about what to do next.

Issue tracking systems

Issue tracking systems (or bug tracking systems) are repositories that track various issues related to the development and maintenance of a software system, along with a user interface that can be used to view, update, and search the repository of issues. As with version control systems, there are many issue tracking products available, which mostly share a common philosophy and differ in their details.

Issues are generally classified in a number of ways, some examples of which follow:

- By kind: bug, feature request, design change

- By status: opened, assigned, closed (i.e., finished), duplicate of existing issue

- By component or module: which part of the system does the issue relate to?

- By version: which version of the system does the issue relate to?

Issues are also generally assigned to individuals or groups, with that assignment changing over time. For example, a feature request might first be assigned to a business analyst, who decides whether the request fits within the scope of the system and negotiates requirements; from there, it might be assigned to a developer to implement, then to a tester to test, and finally back to the customer to do acceptance testing, before finally being closed.

Integrating issue tracking with version control

There is value in integrating an issue tracking system with a version control system. For example, if every issue was linked to changesets of source code changes that were made to address it — and, conversely, changesets were linked back to issues — we would have a fuller picture of the history of a system, which can be beneficial, especially on a large project where people are joining and leaving it over time.